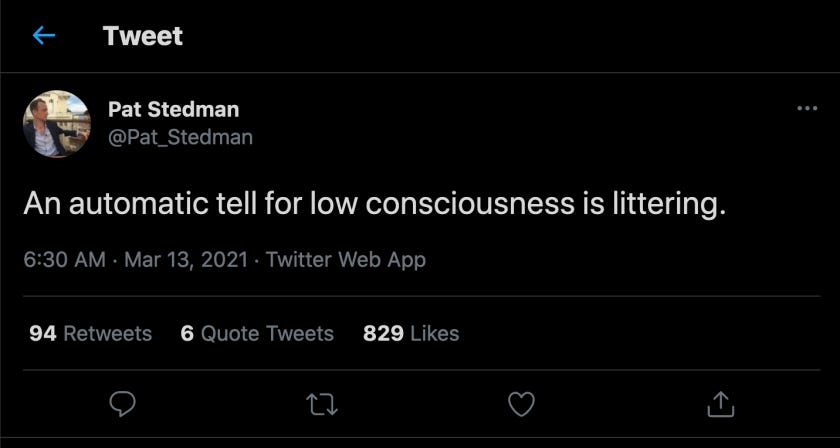

The most stridently asserted opinions will disappear down the memory hole (Pat Stedman example)

What should we learn about the people who lie about medicine?

The most stridently asserted opinions will disappear down the memory hole.

Remember all the hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) truthers from a few months ago? The ones who no longer exist, or seem to exist? The ones who had all the answers six months ago?

I know, I barely remember them either, and probably none of the people who were confidently pitching it do. But I wonder and you should too, "What are they stridently asserting today?" Should we believe it? Why?

What should we take from this episode? I haven't seen any of the voices who were confidently and wrongly asserting that HCQ or this thing or that thing (vitamin c! no, d!) is a magic bullet, talk about how they were wrong, why they were wrong, and most importantly what will change in the future.

There are parallel processes in the past. After the Iraq war fiasco, at least some of the pitchmen, like Colin Powell, went through that process. But the same kind of people, sometimes the same people, who were stridently proclaiming the importance of universal democracy in the 2002 - 2008 era are stridently proclaiming that democracy doesn't matter today, or that it should be subverted. What happened from then to now? Why does no one bring up that episode in recent American history?

Internet memories are very short, even shorter than tweets. When you see people, or a group of people, be wildly wrong, that should affect how you think of them in other topics. Someone can be right in one domain and wrong in another, but being totally wrong one in one domain should make us question what's happening in others.

The same people pitching drug company conspiracies, are forgetting that drug researchers and companies are the entities that have worked best during the pandemic: the previous world record for the development of a vaccine was four years. COVID-19 vaccines happened in 11 month, and would have happened faster with a more intelligent clinical trial process. Pharma companies are among the pandemic's heroes.

For many people, there is a world and worldview that is simple, coherent, and wrong. The simple gather online, where their views rarely have real world impact... unless there are enough of them together. Lots of people spout conspiracy theories, but none of them are closely reading Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories by Rob Brotherton. None of them are saying, "How does this fit into the last 50 years of history?" Online, history doesn't exist. I understand intellectually that many of these people are trying to showcase their "team" and build coalitions. In sports, showcasing that you are a fan of whatever team doesn't have negative and serious real-world repercussions, though, as it can in some domains.

I don't think it's good to have a political "side" as so many do, and choosing a political side, or a political mood, makes people tribal and stupid. Try hard to evaluate things in terms of truth and falsehood, not who is saying them, or whether your "side" benefits. This is tricky, almost no one does it, and it's a valuable way of looking at the world. If I look at a field where the "left" is correct, people call me a Republican. If I look at a field where the "right" is correct, then they call me a liberal or progressive (Nash attributes politics to me that I don't have in comments, others do the same on ephemeral twitter). The labeling of a person or idea as being part of the other side seems psychologically comforting to the labeler. I am like Claire Lehmann, "Some people ask 'what has happened to you?' with respect to my views on matters related to Covid. But I could ask the same of the Right. Since Covid, many Rightists have been anti-free market, anti-tech, anti-border control, anti-personal responsibility, & anti-self sacrifice." I wouldn't agree with all she says there, but she is getting something vital.

We should try to politicize as few things as possible but sadly that does not appear to be human nature. The HCQ thing is an example... when the biggest HCQ promoter got COVID, he got treated with remdesivir and monoclonal antibody therapy, because those treatments appear to work better than placebo. Both, however, are difficult to mass manufacture, and, when his followers get COVID, they are not likely to get the same. When it comes down to what really matters, it's away with the baseless theories and in with the supported treatments. We should be thinking about why that is and what that says about humans, human nature, the Internet, and the tendency to follow the leader.

The will to believe is so strong that it can overcome evidence. What's going on there? I don't fully or rightly know. It's one of these psychological quirks and puzzles that interest, though. Something about the Internet seems to allow or encourage people to do more of this than they used to. It probably feeds on real institutional failures, too. We do have evidence that, "When political parties reverse their policy stance, their supporters immediately switch their opinions too." Most people follow the leader. If the leader says something false, and you say it's true, then you're really a member of the tribe. Anyone can assert something true. To assert something false, you're being in the in-group.

Brandolini's Law applies, stating, "The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude larger than to produce it." Much bullshit can be included in a single 240 character tweet... so much that it may take many paragraphs to show why it is incorrect... by which point the tweeter has moved on anyway... and the HCQ thing is an example of that as well. So is the obsession with vitamins C and D. Bullshit goes around the world before the truth has time to put on its pants. What's really true about a complex matter that's important often doesn't fit in a tweet.

What makes people double down on expressively believing incorrect things? How does this mechanism work? I don't have a good answer, despite the "Follow the leader" thing. It's not IQ. Pat Stedman is ignorant about the history of vitamin C as a purported cure-all (it isn't), but he's not low IQ. The first link in this post goes to a Nash comment thread, in which he baselessly claims "HCQ appears to be taking a lot of victory laps lately" (it hadn't), and "I think we could shaved 30-50% off the whole 'epidemic' if there wasn’t so much political (and Pharma) resistance to what appears to be proving over and over to be a very effective treatment indeed."

It isn't, and it wasn't then... that comment is from August and by then large-scale trials demonstrated that HCQ isn't effective and increases cardiac risk, which is why doctors weren't prescribing it. He does say, "Time will tell," but by then it already had. Nash is not low IQ: you can tell from his writing, and you can tell by talking to him. And neither Stedman nor Nash were in an information-poor environment: both had access to accurate information about the performance of different treatments, and chose to ignore it. "Low IQ" or "stupid" apply to many people baselessly promoting incorrect ideas, but not all of them. Is it just tribalism? Something else? It seems like an open question. Many guys have dubious/unlikely beliefs about what women are attracted to... addressing some of them, and showing what's possible, is one purpose of this blog. Learning anything is partially about learning how to discern what's real and what's not.

Twitter is the eternal now. Maybe claims online are supposed to be purely performative. In evaluating their truthfulness, I'm being the mark, because I'm mistaking Die Hard for a documentary. Few of the people making claims about HCQ were doctors, or had to face the reality of sick people being treated with ineffective or harmful substances. They're just performing. But what happens when there's a large segment of society that's living performance? I guess we're finding out.

I don't expect this to change minds or deepen thinking (disinformation crises are their own thing) but it is worth thinking about who makes testable predictions that turn out to be wrong, and what the response to being wrong is. Is the response to being wrong to double down, and continue making false claims, but with perhaps new and equally wrong reasoning? Or… is the response to being wrong to learn? Is it to shove it down the memory hole (might be the most common reaction... we have always been at war with Eastasia?). Is it something else? Or is it, most likely and commonly, to forget? Within a year, vaccines will be widely distributed and many shameful aspects of COVID behavior will be forgotten. A couple guys have asked me what I've been wrong about, one big one is that in January and early February I thought coronavirus would mostly be a problem in China, to the extent I thought about it at all... damn, that turned out to be hugely incorrect. By March I'd changed my view based on, you know, reality... but that was a big error.

Some guys who were in the game pull a St. Augustine and repudiate their skirt-chasing selves. The way psychology works is endlessly weird, making it also an interesting to field to study. Why are previous claims forgotten? When are they brought back to the fore? Why?

Vitamin d infusions are a good idea, but not a silver bullet, and should be performed uniformly. Fluvoxamine is a more promising drug than HCQ, though also not a silver bullet, but where are all the Twitter pharmacologists on that subject? Why are they so strangely quiet on it? They were busy reading the research nine months ago, weren't they? Where are they now?

Why are they silent?

Paying attention to what many guys interested in "game" and "seduction" say is revealing in terms of why these ideas don't spread further. Many of the people interested in them are not good. "Coolness and status first" is a commonly failed test.

After I wrote the above, I found out that Stedman is nuts enough to have participated in the Jan. 6 attempted insurrection, for which an arrest warrant has been issued. Maybe a guy who attempts to foment treasonous insurrection (here is his indictment) and who also pushes quack cures can simultaneously be a great dating coach. It's not impossible, I suppose. This is the same guy who writes about increasing "access to more beautiful, emotionally healthy women." Yeah, good luck with that.

He also wrote, “As I write this in 2023, only two friends from my life before 2016 have wanted to keep in contact with me: one from childhood, one from college. Two people out of 200.” This is, again, from a man whose coaching business is supposed to help teach men social acuity. He seems to have no idea why people might not like someone who tries to end two and a half centuries of peaceful political power transfer, and a man whose livestreams from that January 2021 period make him sound like a bipolar maniac having a psychotic break with reality.

A reader sent me this, which is pretty funny,

Littering is "an automatic tell" for "low consciousness," but pitching quack medicine that is at best ineffective and at worst dangerous, for a potentially fatal disease, isn't? Participating in an insurrectionist riot isn't "an automatic tell for low consciousness?" How about a felony conviction for participating in that insurrectionist riot? This guy missed his calling: he should be in standup comedy. Or a clown.